How to Read Music Using Intervals and Landmark Notes vs. Mnemonics

Most music teachers teach note reading one of two ways: 1) mnemonics or 2) intervals with landmark notes. Whichever way you prefer, interval recognition is invaluable for producing strong readers. Even students who use mnemonics will become stronger readers if they also learn to recognize music intervals.

What are Mnemonics?

A mnemonic is a memory aid: it uses letters, words, phrases, ideas, or associations to help you remember something. Take the starting letters of whatever you're trying to remember, and make them into a word, or reassign new words to these same letters to create a memorable phrase.

Examples of well-known mnemonics:

How to Read Music Using Music Staff Mnemonics

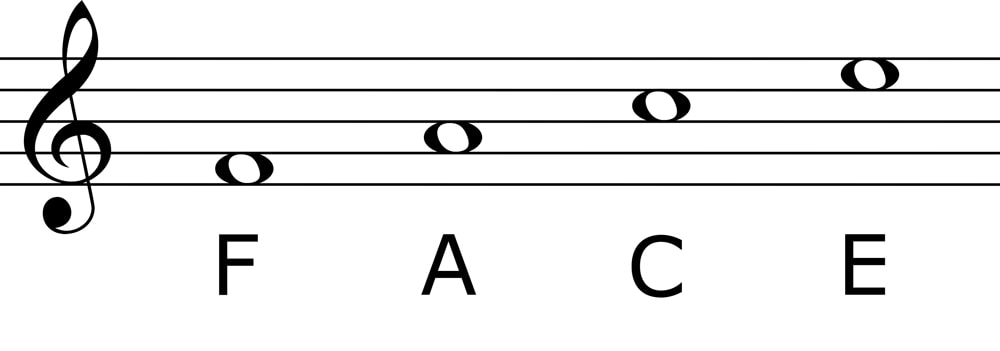

Music mnemonics are based on the music staff lines and spaces. Thousands if not millions of musicians have been taught mnemonics for treble and bass clef note reading.

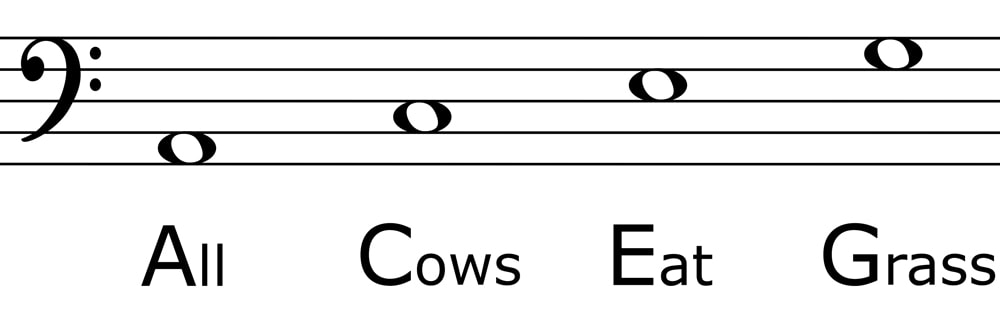

Some of the most common music staff mnemonics:

You can use mnemonics to name any note. See a note on Bass space 3? Think of your phrase and stop at the 3rd word ("All Cows Eat" -- this note is an E).

As a music teacher, I have taught all types of students. Some easily memorize the treble clef mnemonics and bass clef mnemonics, but many others struggle with them. I learned early on that these mnemonics are NOT a good teaching tool for everyone. Here's why.

Why Music Mnemonics Don't Always Work

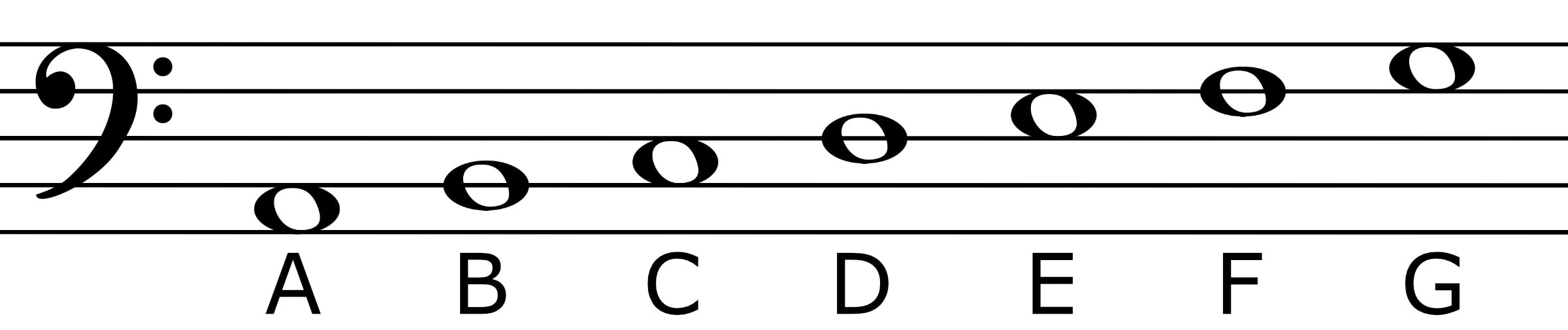

Overcomplicates the Simple Letter Names: The Musical Alphabet is just letters A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, repeated over and over. Every child learns these 7 letters by kindergarten (or before).

If a child can learn the alphabet by age 5 or 6, they can learn where A is on each staff and then go through the musical ABCs to find any other note. Why add more words and phrases when these 7 letters are just fine on their own?

Mnemonic Mixups: Each staff has 5 lines and 4 spaces. For pianists, that's 4 music staff mnemonics. Some students can't remember them all. Many often mix up which mnemonic goes with which staff/line/space.

If a student learns the "Every Good Boy Does Fine" Treble lines mnemonic along with the "Good Boys Do Fine Always" Bass lines mnemonic? Both line notes, and both with "Good Boys" ? It's practically a guarantee that they'll constantly mix them up!

Students end up spending so much time trying to remember which mnemonic to use that they'd be faster at counting up or down the letters. Mnemonics become an unhelpful and unnecessary step that slows them down.

Unrelated to Music: What do Grass-Eating Cows, Good Boys, and Emptying the Garbage have to do with music?? Nothing. With no contextual relationship to music, musical mnemonics seem confusing and pointless.

No Relationship Between Mnemonic and Staff: How do you remember which mnemonic goes with which staff? Most ideas I've heard are shaky at best, like this one: "Good Boys have FACEs, and your FACE is high on your body, like Treble notes." (Okay, so are we saying that our Cows in the bass clef don't have FACEs?)

No Relationship Between Lines and Spaces: Music notes go up the staff in a repeating pattern of line-space-line-space. But with mnemonics, students are taught to think of lines and spaces as separate, unrelated things.

Ideally, students use mnemonics like this:

"The first note is a space, so FACE = F, then the notes step up, so it's F-G-A."

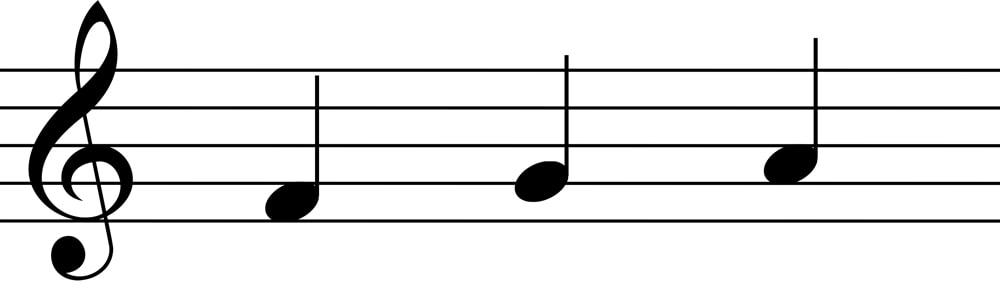

Example: Sheet music shows ascending notes F, G, A on the Treble Staff.

But some students use mnemonics like this:

"The first note is a space, so FACE = F, the next note is a line, so Every-Good = G, and the third note is a space again, so FACE f-a = A."

This slows reading down significantly as sheet music gets more complicated. I have seen students get completely stuck; they are trying so hard to remember the words/phrases that they've forgotten the simple order of the musical alphabet!

No Relationship Between Notes: Students who rely on mnemonics often fail to see the relationship between notes when sight reading.

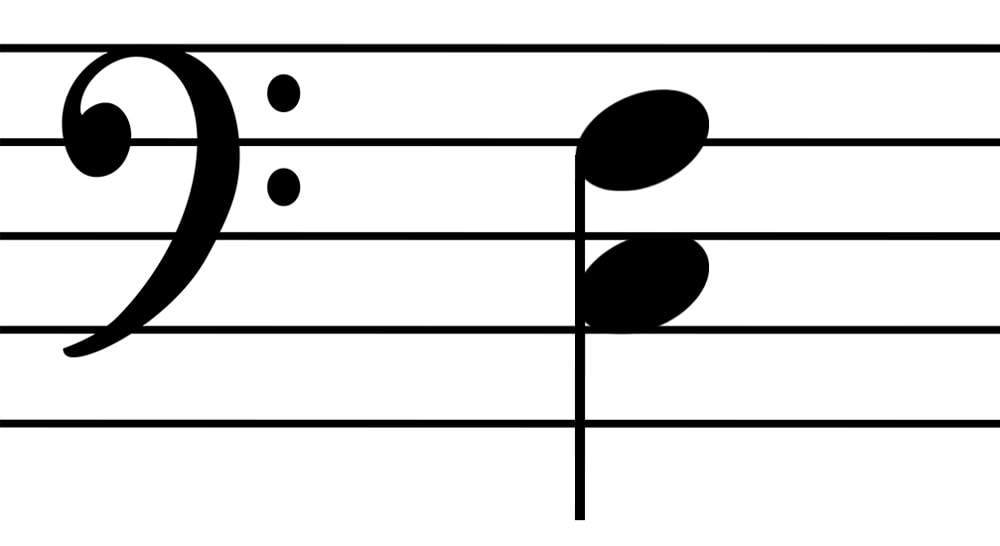

Example: Sheet music shows C and F, played simultaneously. C is the lower note.

Student 1 (trained in staff mnemonics) sees two independent notes that should be played together. They identify each note on its own, then play them together. This may take up to twice as long as Student 2:

Student 2 (trained in intervallic reading) see a harmonic 4th. After identifying just one of the notes, they play it with the 4th above (or below, depending on which note they've identified).

Student 1 does not see the relationship between the notes and has little or no concept of how they will sound together. This student may have a harder time knowing whether they've played it correctly. Student 2 can anticipate the sound of this interval before playing, and when they play it, they will immediately know whether they've played it correctly.

No Relationship Between Sight and Sound: Mnemonics are useful for reading music only. Students thinking through the mnemonics while sight reading are often doing very little listening. They may play through an entire passage without listening to themselves, and then they have no idea what they've just played.

Most mnemonically trained students have no idea how a series of notes will sound together as a musical phrase until after they've figured each one out individually with the correct mnemonic, played it, and then played it all together again a few times. By contrast, an intervallic reader can anticipate how they will sound based on the intervals between them, before they've played a single note.

What Are Intervals in Music?

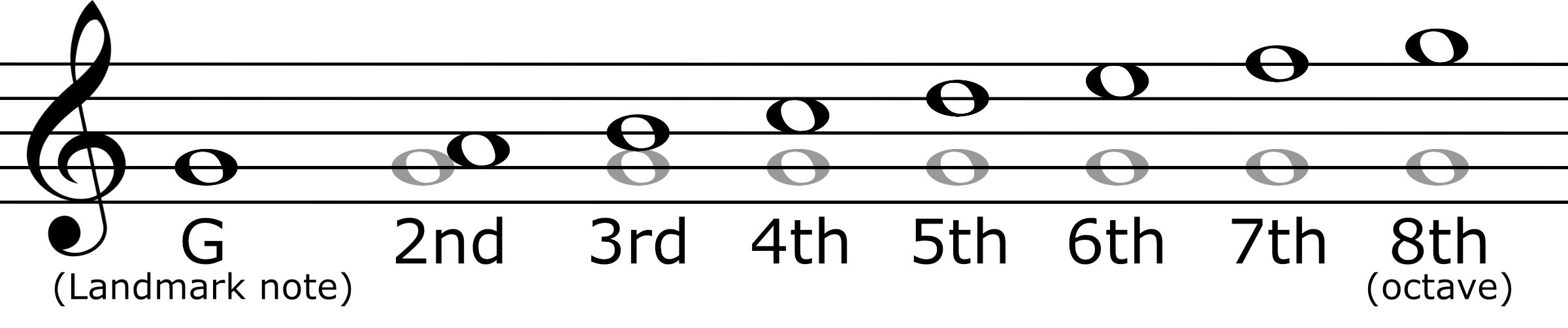

An interval is the distance between notes. Count the letters you see plus any note names in between those letters, and that's the interval.

(This post is about the basic interval numbers, not interval qualities i.e. Major, Minor, and Perfect.)

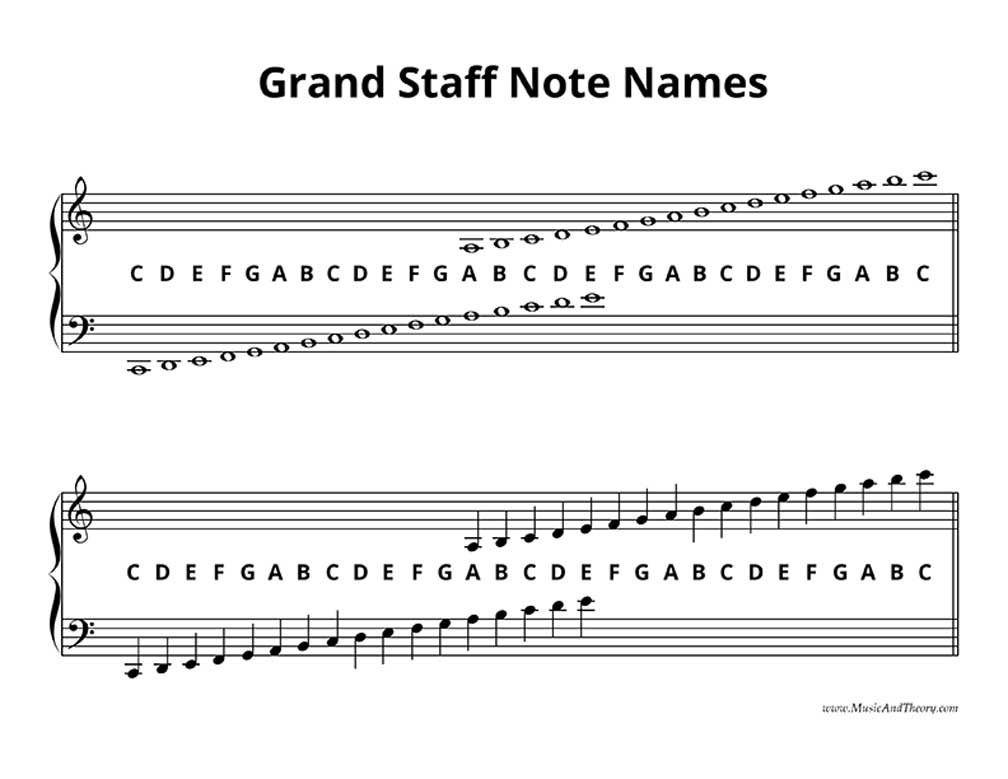

How to Read Music Using Intervals and Landmark Notes

Intervals are a fantastic way to teach note reading because they use letters and counting: two concepts that even most 5-year-olds can understand.

Start With a Landmark Note

Start by memorizing just 1 landmark note for each staff. The most commonly chosen ones are Treble G and Bass F.

Treble Clef is the "G Clef" because it wraps around the G line. If you close the circle in the middle, the bottom part looks like a fancy letter G.

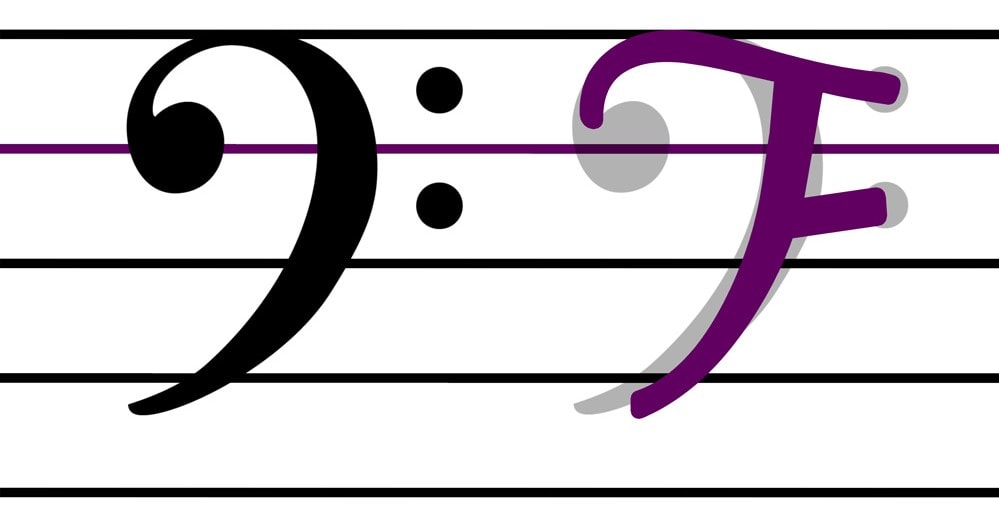

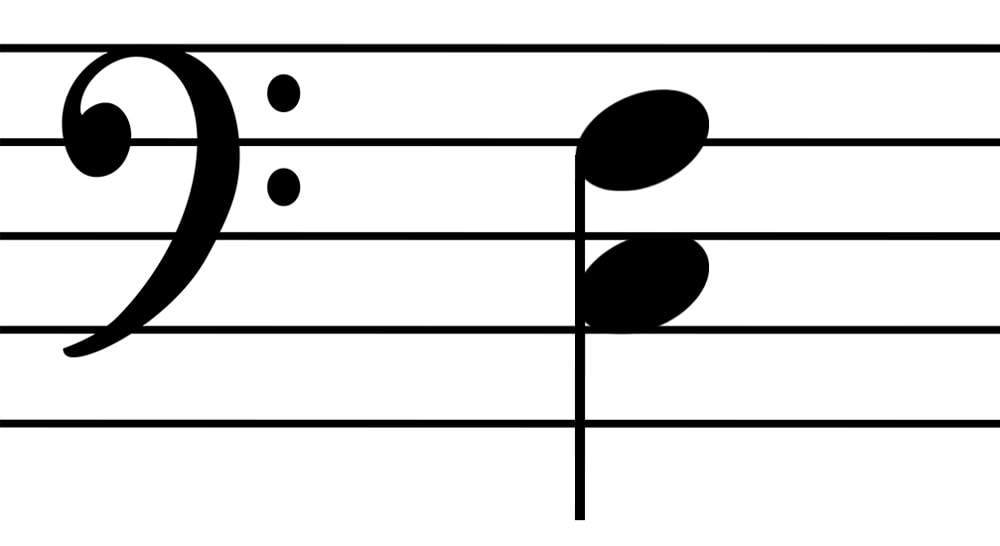

Bass Clef is the "F Clef" because the two dots are on either side of the F line. If you draw lines connecting these dots to the clef, it looks like a curvy letter F.

Treble G is the 2nd line up. Bass F is the 2nd line down.

Other good Landmark notes include:

When music notes move higher or lower on the staff, it helps to have 1 or 2 additional landmark notes memorized. But for the most part, having just these landmark notes memorized is all you need to find any note using intervals.

Then Count Up or Down the Staff

Using just Treble G and Bass F, or whichever other landmark notes you have chosen, you can find and name every note on the staff.

Count up or down the lines and spaces from your Landmark notes to figure out the distance (interval) between the note and the Landmark note.

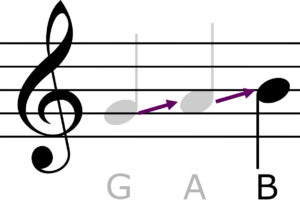

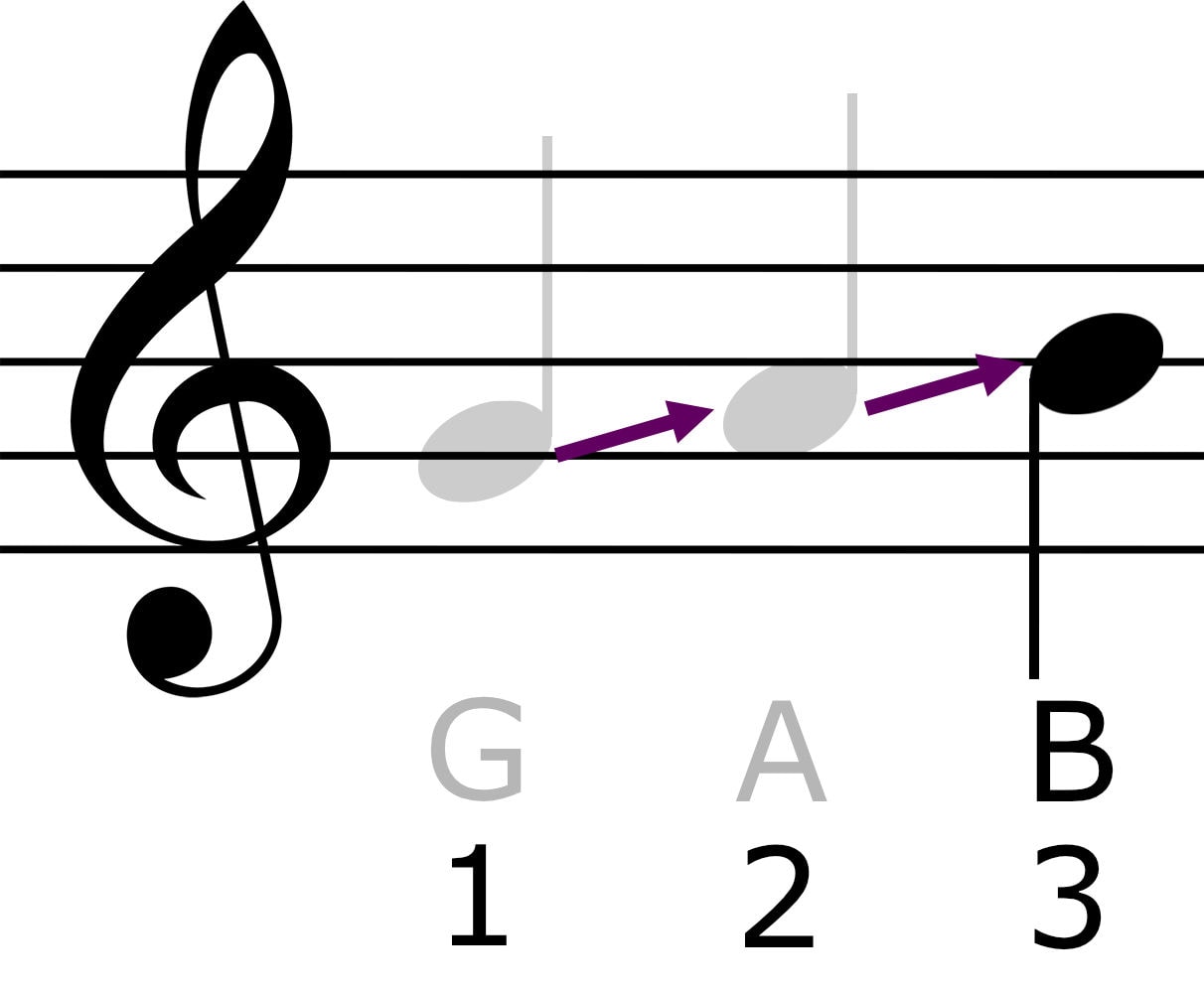

See this note on Treble line 3?

Start from G and count up: G line, space, line. 1, 2, 3. This note is a 3rd above G.

To play this on piano, count the keys along with the staff lines and spaces. Start from the G key and count up 3 keys to play B.

Why Intervals Are Good for Music Note Reading

Simple Letters, Simple Numbers: Most students know the first 7 letters of the alphabet before they begin music lessons. This makes it very easy to teach them the musical alphabet. (Instead of all 26 letters, they just have to remember 7!) Most students also know their numbers and the basics of counting before they begin music lessons.

These two things that students are already familiar with -- basic letters and basic number counting -- are the foundation of intervals. Once students know the starting point on the staff, all they have to do is count forward or backward in the alphabet.

Not Easily Mixed Up: Letters and numbers are familiar concepts, and schoolteachers already reinforce these concepts daily. It's unlikely for students to mix up the 7 letters of the musical alphabet and the basic number order.

Students who mix up their letters or numbers will benefit from extra tutoring or parental help, which will help them both in school AND in music lessons.

Intervals Are a Musical Concept: Counting intervals has a clear, direct application to reading music notes on the staff AND to ear training, in which musicians learn how to hear music intervals based on how they look. It's also directly related to the piano keyboard, as each staff line or space represents a white key on the piano.

Intervals Are Counted on the Music Staff: Students count the lines and spaces directly on the staff. The distance between two notes on the music staff is the basic interval. Further, unlike mnemonics which are different for each staff, intervals are counted exactly the same way on the Treble Staff as they are on the Bass Staff.

Lines and Spaces Are Counted Together: Mnemonics separate lines and spaces into different phrases, while intervals count up (or down) the lines and spaces together. Whether your starting note is on a line or a space, it's the same: Count line-space-line-space (or space-line-space-line) until you get to your ending note, and that's your interval.

Intervals Show the Relationship Between Notes: Music notes are rarely independent things. While students who rely on mnemonics often fail to see the relationship between notes, students trained in reading intervals can see how each note relates to the one before it.

Referring to our earlier example:

Example: Sheet music shows C and F, played simultaneously. C is the lower note.

Student 1 (trained in staff mnemonics) sees two independent notes.

Student 2 (trained in intervallic reading) see a harmonic 4th. They can anticipate the sound of this interval before playing, and when they play it, they will immediately know whether they've played it correctly.

"Interval Shapes" Become Easy to Recognize: Children learn basic shapes such as circles, triangles, squares, etc. from a very young age. Musical intervals on the staff each have a distinct appearance that, with time, can become as recognizable as these basic shapes.

Students who are trained in intervallic note reading learn to instantly recognize a 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 8th, etc. With instant recognition, they can find them more quickly on the piano.

Conversely, students who rely on mnemonics think of the notes independently and will often take longer to identify and play them.

Intervals Can Be Used By Solfege Learners: Music intervals are the same whether a musician refers to the notes as "C D E" or "Do Re Mi", and whether solfege is taught as Fixed-Do or Moveable-Do. Therefore, it has a wider global use since many countries and cultures teach solfege instead of the musical alphabet. By contrast, the standard music mnemonics aren't applicable to solfege at all.

Intervals Have to Do With Sight AND Sound: Unlike mnemonics (useful for reading music only), Intervals are use for visual AND aural recognition, and each reinforces the other. A student can learn to recognize a 2nd, 3rd, 4th, etc. by sound as well as sight.

A musician who reads musical intervals can hear a melody line or harmony in their head before they've played it on their instrument. This is usually done by associating intervals with popular melodies, such as:

Being able to hear the music in your head before you've even played it is a huge advantage for sight reading! It helps you know what sounds to expect when you're playing something new, and it makes it easier to know whether you played it correctly the first time.

Intervals Are Kinesthetic, Too: Learning a musical instrument is a kinesthetic experience. Musicians physically play their instruments, so they have to know how they feel. Pianists learn to feel how far apart certain key combinations are. While learning what a 5th looks like on the staff, pianists learn what a 5th feels like in their fingers. This connection between sight and touch strengthens kinesthetic learning.

This improves a valuable life skill for those who struggle with kinesthetic learning, AND it helps students who excel at kinesthetic learning with their visual learning skills.

Intervals Help Students Master Sight Reading Faster: Learning to instantly name all music notes on the staff takes a while. But sight reading is NOT about naming the notes. The point of sight reading is to read sheet music.

Sheet music is a written record that makes it so music can be preserved and shared. Assigning note names to all the little black dots on the page lets us communicate with other people about what the paper says. But whether Treble Space 3 is called "C" or "Do", it represents the same musical sound.

If a student sees a perfect 5th, and they know that the lower note is G, they don't have to remember in the moment that the higher note is called "D". All they have to do is find G on their instrument and play the 5th above.

Using this strategy, many students become skilled sight readers even before they can name all the notes individually. Their knowledge of intervals lets them read more challenging music sooner, which accelerates their learning and enhances their musicianship skills further!

If music students learn to recognize basic intervals in music, sight reading will definitely improve. Even students who use mnemonics will become stronger readers if they also learn to recognize music intervals.

Intervals Introduction Collection from Music and Theory

The Music and Theory Intervals Introduction Collection can teach the students in your studio or classroom how to recognize music intervals.

Created for students of all ages (both children and adult), this collection teaches piano students to recognize Harmonic AND Melodic Intervals including 2nds, 3rds, 4ths, 5ths, 6ths, 7ths, and 8ths (octaves).

Students will learn to recognize these music intervals on the Staff, on the Piano, and by Note Names through a variety of teaching approaches, including:

Ledger lines are included to strengthen interval recognition for notes above or below the 5 lines of the music staff. Various note values are also included to help students recognize intervals however they may appear in their sheet music.

This extensive collection includes:

- Over 100 unique worksheets

- ANSWER KEYS for all worksheets

- 39 instruction pages

- 13 unique At A Glance pages (helpful clues to identify each on-staff interval instantly!)

This fantastic teaching tool comes with a Studio License: buy it once, and you can share the ENTIRE COLLECTION with as many of your own students as you want from now until you retire!

Ever since I introduced these intervals pages to my students, I have seen a HUGE IMPROVEMENT in their music reading skills. I look forward to hearing how it's helping your students learn to sight read more fluently.

Have you gotten the Intervals Introduction Collection yet? Do you have ideas on how you plan to use it for your own students? Please share in the comments!